Imaginary Mobilities: Journeys in Cardboard and Clay

Conversation between Janet Abrams & Shannon Goff

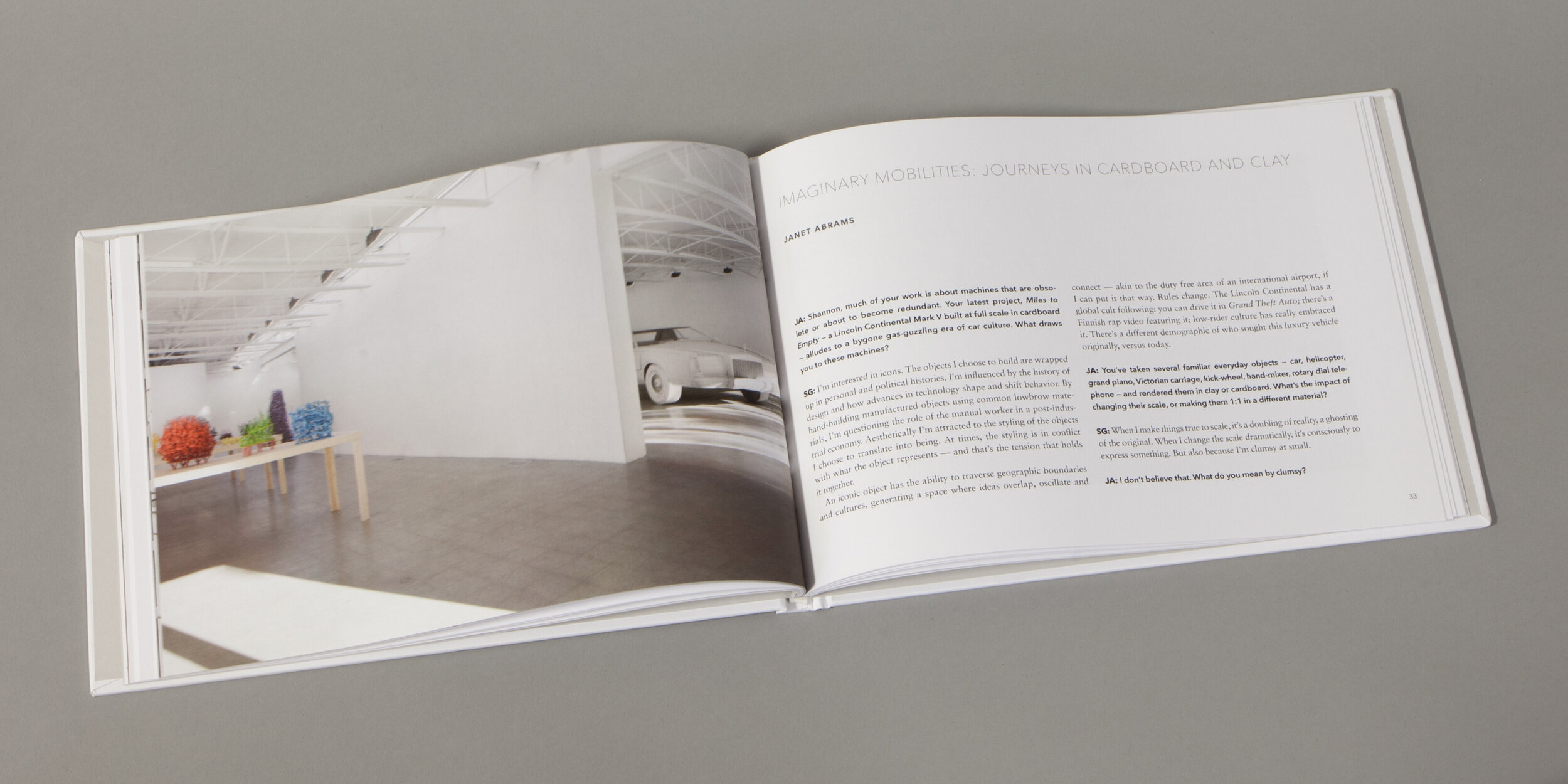

JA: Shannon, much of your work is about machines that are obsolete or about to become redundant. Your latest project, Miles to Empty — a Lincoln Continental Mark V built at full scale in cardboard — alludes to a bygone gas-guzzling era of car culture. What draws you to these machines?

SG: I’m interested in icons. The objects I choose to build are wrapped up in personal and political histories. I’m influenced by the history of design and how advances in technology shape and shift behavior. By hand-building manufactured objects using common lowbrow materials, I’m questioning the role of the manual worker in a post-industrial economy. Aesthetically I’m attracted to the styling of the objects I choose to translate into being. At times, the styling is in conflict with what the object represents — and that’s the tension that holds it together.

An iconic object has the ability to traverse geographic boundaries and cultures, generating a space where ideas overlap, oscillate and connect — akin to the duty free area of an international airport, if I can put it that way. Rules change. The Lincoln Continental has a global cult following: you can drive it in Grand Theft Auto; there’s a Finnish rap video featuring it; low-rider culture has really embraced it. There’s a different demographic of who sought this luxury vehicle originally, versus today.

JA: You’ve taken several familiar everyday objects — car, helicopter, grand piano, Victorian carriage, kick-wheel, hand-mixer, rotary dial telephone — and rendered them in clay or cardboard. What’s the impact of changing their scale, or making them 1:1 in a different material?

SG: When I make things true to scale, it’s a doubling of reality, a ghosting of the original. When I change the scale dramatically, it’s consciously to express something. But also because I’m clumsy at small.

JA: I don’t believe that. What do you mean by clumsy?

SG: My fingers don’t work well at minutiae.

JA: Are you working out how the original object was made, by re-making it?

SG: I come to understand why an object came to be, concurrent to making it, but really I invent how to make it. I’m not replicating; I’m translating. I was going to put a floor in the car, then realized it didn’t need one. I also didn’t make the keyhole. The doors don’t open. I left the bone structure of the honeycomb cardboard visible, under the dashboard area, so people get an idea of what it really is. It’s a sculpture of a car.

JA: Did you get an actual car, and draw detailed sketches from it, or from photos?

SG: Tom [Lauerman, her husband] found a 1/64th scale model of the car, which cost around $70 and had to be ordered from The Netherlands. We sprayed it with white paint, then Tom scanned it and put it through this slicing program 123d make, which helped me figure out the umpteen layers I had to project, trace, cut, and stack to make the bones of the car. That’s not how I usually work, but I was afraid to start, because I’d never made anything that large, so Tom helped me. I rebuilt the roof here in a very short time, the way I normally build things. He would never build something like that. But it was so much more right for the car because it was solely my problem solving.

JA: Tom’s very interested in digital fabrication technology, but are you? Isn’t your work really still about the hand?

SG: It is, but that’s not to say I think the digital is devoid of the hand; it’s just different. I’m aware of the digital landscape because Tom’s always talking about it. But it’s too removed for me — too many filters to go through to produce something. I’d rather just deal with the material. The bones of the car are a combo of hand and digital fabrication, but I’m far more interested in the skins. This car was all about the voguish details, like the side vents that vented nothing, the spare-tire-less spare tire bulge in the trunk! Very ostentatious…it’s a satire in cardboard, with reverence for the original.

JA: Did you cut everything out at once, or work on a specific zone of the vehicle, and fill out all the details? Or do you work steadily upwards?

SG: I started with the bones crafted from layers of jigsaw-cut honeycomb board. I worked from the inside out, then the outside in, and from the ground up. While I was building the structure, I was also building the axle and tires, worrying later how I would mount the body onto that. I built the outside skin first, and the inside skin more recently.

JA: How much of the latter is visible?

SG: That depends how much the viewer wants to manipulate their body to see inside!

JA: Now that you’ve made this car, when you stand back, how do you feel about it?

SG: “When is it ever done?” There’s so much detail work, and I’d happily have kept going: edge the interior to bring out more of the lines. If the car was to travel, I might do something different for each show: put an engine in it for one, some custom luggage for another.

JA: The car, the helicopter: there’s a machismo to them. I can think of several other women artists who have remade or reinterpreted cars recently: Liz Cohen, Rose B. Simpson, and Jude Tallichet. Why are you drawn, as a woman, to making these ‘guy’ kind of objects?

SG: I have a personal connection to the Lincoln and grew up in car culture, here in Detroit. The helicopter is more of a fantasy object although I did once meet a friend’s dad who had a Bell 47 and took me up for a ride…fascinating and terrifying yet peaceful and surreal.

Cars and helicopters like lawyers, guns and money…ha! I make what I have to make. I don’t set out to fight machismo but it’s empowering to craft large objects…somewhat parallel to the birthing process. I do enjoy poking fun at macho stereotypes.

JA: Why did you choose to make the Bell 47 in particular?

SG: It was the iconic helicopter of the Korean War, and the first for civilian use. To me, helicopters represent escape, convenience, luxury, emergency. When I made it, I was just out of grad school, living at my parents’ house, doing dumb jobs. Didn’t know what I was going to do next. I was thinking: How can I escape my current situation? The All-Star Game was going on at Detroit Tigers stadium, so there were helicopters flying all over the city. It made me paranoid about living in an age of surveillance. More abstractly, I was thinking about the relationship between a paper airplane and real airplane. As a kid, when your parents got a new refrigerator, you’d get this huge cardboard box, and could make anything you wanted out of it. It’s about potential and imaginary mobility. The helicopter also reminded me a little of an absurd mobile in a Dr Seuss book: a cartoon come-to-life.

JA: I sometimes wonder whether you’re honoring or parodying these pieces of equipment. Is it about nostalgia for previous eras of technology, or is it mechanical action, specifically, that captures your imagination?

SG: Honoring and parodying simultaneously…peppered with a bit of nostalgia for a simpler time. Mechanical action abstractly captures my attention, but it’s the direct one-on-one relationship with objects and their use that keeps me engaged. I’m attracted to the tactile invitation of certain gadgets which, when used over time, create a muscle memory that becomes sentimental. My grandfather had a Super 8 camera, all these tapes, and a back-to-back reel. You could control it yourself, create a mini early-stage GIF. It made this clicking sound. If I were to re-experience that sound, moving my wrists a certain way, and moving my fingers on the turn knob, it would really put me back in that place.

JA: Are there contemporary industrial design objects that have that appeal? An iPhone made out of cardboard might not have much interest given that its functionality is in the software and its interface, rather than in any mechanical action. What will your daughter Marcella look back on, if she only handles objects that provide access to software systems, and intangible networks?

SG: Tom’s always printing out gears and building machines right in front of her. Lego and MagnaTiles come into play, as does clay of course. So she’s experiencing the tactile in many ways. One day I took her to pick out a toy, and she chose a pink phone like the one I made at Kohler: a push button, not a rotary-dial. Notice that the iPhone has an old style phone as the phone icon, not a flat rectangle.

JA: How do you shift back and forth between working in clay versus in cardboard? What insights result from that dovetailing?

SG: In many ways, my clay work and my cardboard work are antidotes for each other. One is made to protect and transport the other. But cardboard allows me to engage more physical space. The time investment is usually great and progress slow and steady. But the oscillation back and forth between these materials yields an overlap where things open up. Cardboard’s physical structure gave me ideas of how to build differently with clay. They have many similarities but also distinct differences. I didn’t set out to be an artist who works with cardboard, but the more I worked with it, the less I thought of it as an intermediate material. Like clay, cardboard is abundant, recyclable and easily workable: it can be cut, torn, folded, compressed, laminated, peeled, or woven. Also like clay, it can be smushed into place, directly with the hand. Like wood, it has a “grain” orientation, due to the direction of the corrugation, which can be exploited for structural or textural effect. It’s a planar material, not unlike a sheet of plywood or a slab of clay. No matter what material I find myself using, I can’t help but view it through a ceramic lens. My homing pigeon tendencies always keep me returning to clay.

JA: You were working on the ceramic pieces during the same period you were building the car. What was that like?

SG: In the case of the Hilberry show, the ceramic work felt like a manifestation of the nervous system, the mind that’s operating while this larger object was coming into being. The clay pieces are very free and spontaneous, like sitting down to draw. I used to spend only 2-3 hours on them, but more recently, I’ve spent 3 to 5 days on each one, working on several at the same time. They’re something I can maintain with my current lifestyle — with two young children. I like challenging gravity in making those pieces, but shipping them is just brutal. Crafting such fragile work is a craft in itself, and can actually take longer than actual making and firing process.

JA: So why do you keep on working with clay?

SG: I like the direct relationship to building an idea out loud. I enjoy its range — clay can be as clean as it can be messy— and its responsiveness. It’s a stubborn material — deceivingly giving, but actually it does what it wants to do. In a review of a recent exhibit at Cherry and Martin in LA, one of the artists referred to it as “Ceramics — the Gambler’s Art.” I thought that was very funny. You have to be a little “off” to want to work with it. Clay is immediate…an apparently simple and delicious material. At any stage of the game it can destroy itself. It can come together quickly and fall apart even quicker — or last a lifetime. I tend to ask it to do things it isn’t meant to do: teasing it, instigating potential collapse or failure. Many of the recent abstractions are built on kiln shelf fragments. Building upon loss…

JA: Have any of them broken?

SG: Some break, and I spray more glaze on and re-fire them. Some break, and I just accept the breakage and paint it bleeding with nail polish.

JA: The paper clay pieces are starting to have distinct sectors to them, rather than being bundles of what I see as “connective tissue.” Interesting that you referred to them earlier as resembling a “nervous system.”

SG: The most recent ones feel more like pictographs, or symbols for a language. Earlier ones were more architectural. Some of the pieces I showed in 2012, I’d made around the time of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, which inspired them to have “legs.” They reminded me of a sinking, spewing rig. Then they put that big boom out — like a tampon-snake — to soak up the oil.

JA: Good God, what a lovely image, not! I see architectural, even Gaudi-esque shapes in the earlier pieces, but also a quality of filigree, a translation into clay of the manual dexterity evident in your cardboard work: tremendous skill with an Exacto knife, cutting out the representative parts of the machine. Like dressmaking, almost.

SG: Pattern-making, for sure.

JA: Looking at your work, the words that come to mind are intricacy, fastening, accumulation, repetition. The tabs on the grand piano keys were a clue for me. Did you have those dress-up doll kits as a child, with folding tabs to keep the dresses in place over the bodies?

SG: Absolutely, I loved those. Fastening relates to the car: there’s this assembly line, where you’re fastening two things together. In the latest ceramics, there’s also the idea of assembly, by glazing two or more pieces together. One clay piece has four or five pieces fastened together — pewter on orange legs, a white cloud on a blue pond — all scraps of another piece I was about to jettison, but decided to breathe new life into.

JA: Curious that they’re ad hoc collages of other pieces that didn’t work out, because they actually seem more composed, than some of the ones you made more serendipitously. You have funny names for things: “cloud,” “pond,” “legs.” You really do personify, anthropomorphize them. Is there starting to be a convergence between the drawing, the cardboard, and the clay? Are you still drawing regularly?

SG: They are composed…of outcasts. I await the collision of drawing, cardboard and clay. I started a series a handful of years ago, before my daughter arrived, that’s a true convergence of all three. But that project has been on the back burner.

After being so physical, with the car, it’d be nice to be flat again. Normally I draw as a preliminary: I’d make a 4” x 6” “doodle-car” that conveys the feeling I want to capture, then figure out how to get that gesture into the sculpture. Now I want to reverse that process: look at what I’ve made, then draw them.

JA: Are you constantly notating new pieces you want to make, in a notebook? Or is it very distinct, which objects you decide to build, after you’ve drawn them?

SG: I can’t help but want to make everything. Some ideas stick and get louder over time. I’m more drawn toward making something that has a kind of history I can connect with. The time investment in cardboard is different than with clay. Clay is liberating as a drawing material. The material is the structure, the line itself. With cardboard, the line is often created by an intense infrastructure that demarcates where two planes almost meet.

JA: There’s an incredible vibrancy to your ceramics palette, yet your cardboard pieces are almost monochrome, the color of the cardboard. Your drawings, which I love, are black ink on white paper: their line quality has spontaneity, and a jaggedness reminiscent of the line produced by a hand pulling a sharp knife through a recalcitrant material. Your earlier machines seem closer to the style of your drawings than the current cardboard car.

SG: That’s intriguing, because when you see it up close up, you realize how very hand-made the car is…wavering line and all.

JA: The raw clay pieces a new development. How did they come about?

SG: The Telegraph Collective, of which I’m a member, was invited to do a show at UC Northridge’s 4000 square feet gallery [Christian Tedeschi, another TC member, teaches there]. I had access to a lot more hands — student helpers who rolled out the coils — so I could do something I hadn’t had time for: make one of the ceramic pieces really large. The piece was made of 250 lbs of clay, using scrap granite as the base. On the second day of the four we had to prepare the show, I began to think it was a terrible idea. It might implode, then I’d have nothing. But in the last few hours of the last day, something happened, because of the scale it had grown to. I knew it had to be as tall or taller than me, to create this 1:1 relationship to my body. Until then, most of my ceramics had been table bound, but all of a sudden, it was something that was looking back at me. I was pregnant, but I wasn’t thinking about my belly when my I was working with my hands and my focus above my head. I ended up calling it Madre.

JA: You’ve been pitting yourself against large objects for a while; now you’re pitting yourself against your own body. What was the inspiration for the next raw clay piece, made at the Susanne Hilberry gallery?

SG: I had to decide what to put in the back alcove. I didn’t want to put actual drawings in there, because I felt everything was a drawing — the car is an inflated drawing, the ceramics are all drawing. I made the raw clay piece to channel my grandfather, using a map of the Campus Martius in downtown Detroit, the real hub of the city, as the beginning ‘drawing’ on the bottom of the piece. As I was building it, I suddenly realized “this is Susanne in one of her big skirts, coming round the corner.” She was larger than life and very much considered the doyenne of the Detroit art scene. It uses 150 lbs of clay, but you can see right through it: it engages space without closing it off.

JA: Paper clay, raw clay, cardboard: what connects these bodies of work?

SG: Drawing…the process of drawing out loud. The hand-built. Transportation, journeys, mapping. Elevating the lowbrow. Fragility and ephemerality, especially in the temporary, unfired clay work — being afraid to sneeze around it, yet really enjoying it while it’s there. You can enjoy this but you can’t keep it! There’s a shelf life to the cardboard car, too: the material will degrade over time.

JA: Yes, you seem to be flirting with fragility, across all three types of materials. In your cardboard works especially, you’re often alluding to the inevitable obsolescence of things on this planet. Things do wear out.

SG: Ideas and materials do wear out but they can also be re-imagined and repurposed.

JA: There’s this ongoing thread in your work about loss and memory.

SG: Memory and loss, but also hope. The show at the Hilberry Gallery became a lot about life and death: about my late grandfather, who owned a Lincoln Continental Mk V; about Susanne Hilberry, who was still alive when I started working on it, but wasn’t doing well; and, sandwiched in between, the birth of my son Felix in May 2015.

JA: What are you thinking of making next?

SG: Part of me thinks of making the Honda CVC, a little egg of a car that came out the same year as the Lincoln, a precursor to the Honda Civic. That car got 40 miles to the gallon, while the Lincoln was getting 9-10 mpg, but no American wanted to hear about it. The CVC was 9 feet long, whereas the Lincoln’s hood is 8 feet long — just the hood. Making this very macho car in cardboard seems like a very American thing to do. But to make two cars, have them face-off in a big space, and be able to compare and contrast them — that would be the ultimate counterpoint. Having lived in Japan, it would also be completing circle in another way.

I think about how we gain and lose mobility over a lifetime, and the potential vehicles that could be employed in such a body of work.

I’ll leave you with the phrase “Cuckoo Clock”. That’d be a way to bring color back into cardboard. Can you imagine the walls of the Hilberry gallery covered in Cuckoo Clocks?

JA: You’d think you’d landed in Switzerland! There’s a vein of cartoon-like inventiveness and mischievousness in your work: it’s comic and elegiac at the same time. Cartoons seem quite an important part of your artistic subconscious. You showed several, especially from the early 1970s, in your recent lecture at the College of Creative Studies.

SG: I love those cartoons. They were on back to back on Saturday mornings: the genius of the Fat Albert junkyard band, coupled with the inventiveness of the Flintstones, and the forward-looking nature of the Jetsons. You’d go all the way from the Stone Age to the Atomic Age, with people flying around in cars using proto-iPhones: “Press this button for this meal.” When I thought about the car having no floor, I thought about the Flintstones’ vehicle, how they got around on pedal power. I love how simple, green and silly, their solutions are: a pelican’s beak as a washing machine for clothes, or a bee inside of a clamshell as a razor. It’s almost like my 4 year old daughter’s imagination come-to-life.

JA: So is that what your art is about? A kind of optimism, that’s in those cartoons?

SG: Comedy is never without its volte face of tragedy. I reconfigure things from the past in order to reflect on the present, and the potential future. Miles to Empty is a story of personal triumph, regional disaster, and global change. It asks for an acknowledgment of history, an inventory of the present, and a directive for the future. To be able to project the same optimism as those iconic, classic cartoons would be a gift.

Janet Abrams is an artist and writer, based in Santa Fe.