Shannon Goff and the Luxury of Carton Ondulé

by Sarah K. Rich, Art Historian & Associate Professor of Art History at Penn State University

On June 18, 1984, the New York Times published an encomium to cardboard penned by one Theodore Ley, alumnus of Columbia University’s engineering program and onetime president of the Universal Corrugated Box Machinery Corporation. Irritated when a Times reporter had used “cardboard” as a term of derision (the reporter had complained that some jargon in the field of economics offered “all the charm of corrugated cardboard”), Ley waxed poetic as he came to the defense of his life’s passion and chief source of income:

“Corrugated cardboard (or just plain corrugated, as we aficionados prefer to call it) has not only charm but beauty of form, majesty of strength and the glamour of exciting products descending upon us from all parts of the world. If one were to take a razor blade and slit a piece of this board at right angles to the corrugations, the “flutes” (the box artisan’s term) so exposed would have a perfection of form comparable, indeed, to the breasts of Venus, and worthy of being called a work of art. Perhaps the rhythmic beauty of this material is better expressed by the French name for the corrugated box—carton ondulé, evoking images that might well have been delineated by the music of Ravel and Debussy. [It is] an enchanted garden where the goddess of the package plays upon her flutes to charm the weary traveler and embrace his shipments in her protective arms.” (1)

And so, with this bit of continental pinky-raising, Ley slyly confirmed exactly what he claimed to deny. Inviting the reader to enjoy the mismatch between his accent aigu and the humble reality that is cardboard, Ley acknowledged how totally weird it is to love cardboard. After all, not everyone can muster enthusiasm for substances like corrugated… or duct tape, ball bearings, aluminum siding, or any other industrial material that usually serves to augment other, more distinguished products. But to those that can, no metaphor or claim epic narrative seems too grand. Consider the less poetic, but no less effusive eulogy to cardboard authored by Harry Bettendorf, publisher of the trade periodical Paper Board Packaging and media mogul (within the paper products world) to whom most executives of American corrugated companies were in some way connected at mid-century:

“Man could not have achieved his present high level of mental, spiritual and physical welfare without paperboard, for the paperboard box today is a vital key to orderly and sanitary transportation and distribution of goods….Without the mass production box, there would be no mass production…we’d move and count things in piles instead of units; in in general we’d ‘coolie’ our way through life. [O]ut of the piles, confusion and dirt of the earlier period came the cleanliness, order, precision and efficiency of mass production goods through the employment of mass production packages of paper board.” (2)

Indeed. Upon cardboard was civilization founded.

I’m starting with such passages in part because, as their authors knew, they abrade against the more typical perception of cardboard as a debased or humble substance (more about that in a moment). Instead, they confirm some of the ways in which cardboard has indeed been essential to late industrial capitalism, and the same time, the silliness of their rhetoric captures the realities of capitalist discourse. These two passages, after all, approximate the citational excitement required by Management at industry conventions and employee retreats. This is the kind of love capital lavishes on stuff instead of on the people who actually produce or work with it.

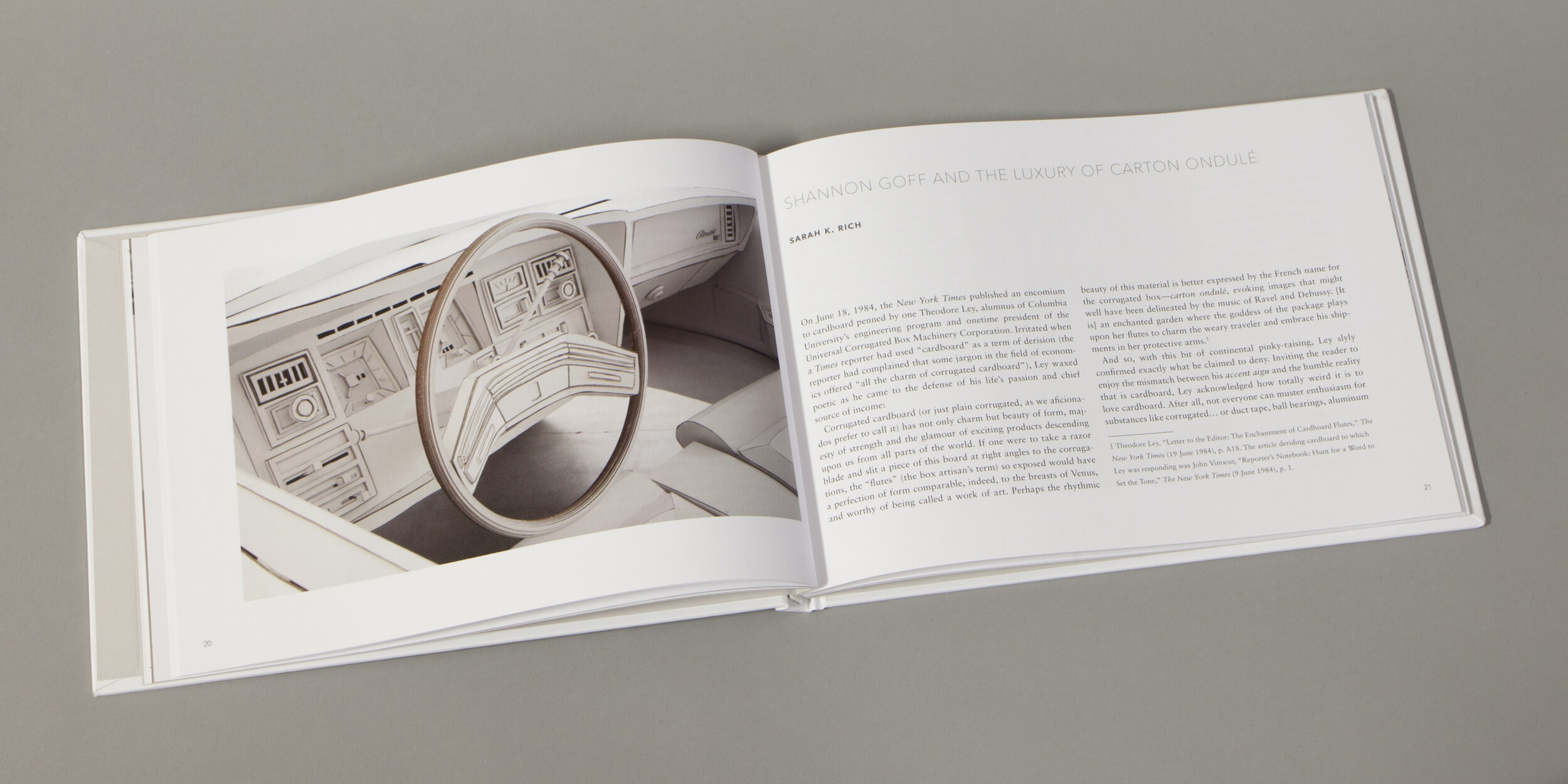

So when Shannon Goff chooses cardboard as the material with which to make a giant Lincoln Continental Mark V (an object that was preceded in previous years by a Goff’s corrugated helicopter and a cardboard carriage), the artist delivers a sort of perverse paean to cardboard and, more important, to the broader consumer culture it represents. In the process, it stages capitalism’s capacity to fetishize, to turn any substance into a fantasy of wealth, even if the source of that wealth is as flimsy as paper.

Goff’s work recognizes that corrugated cardboard is, like a car, an industrial artifact that was invented for purposes of transportation. But while vehicles typically transport people, cardboard boxes came into existence because they (unlike heavy and expensive wooden crates) make it easier and cheaper to ship commodities. Indeed, the symbiotic connection between cardboard and consumer goods is now so powerful that economists like Alan Greenspan have used the health of the cardboard industry as an index for the economy in general. (3) Companies need more cardboard when production is high, the reasoning goes; the more that cardboard boxes are demanded and thus produced, the more consumer that other goods are probably getting produced, shipped and bought.

This link between consumer culture and cardboard has become more obvious to shoppers in the age of digital purchasing. Previously, corrugated often occupied the backstage of consumption. Factories and wholesalers shipped cardboard containers of bulk quantities of products to stores in cardboard retailers unloaded boxes at the store’s loading dock, empty the boxes of their contents and display those contents on the shop floor; the cardboard was broken down in the back room for discreet disposal. (Note that Warhol’s painted plywood Brillo Boxes of 1964 did not imitate packaging that a shopper would see on the grocer’s shelf; rather, they imitated the cardboard boxes that trucks delivered at a store’s loading dock. Perhaps Warhol worried that the individual Brillo boxes from the shelf weren’t large enough to qualify as sculpture. Perhaps he just wanted a bigger package.) Today a mere mouse-click (and a lot of hidden labor) results in a cardboard box being delivered to the consumer’s doorstep. The buyer herself empties it of its payload, breaks the box down and leaves it on the curb, hoping that her roadside offering to the recycling gods will be accepted as penance for the conspicuous consumption just committed.

But in spite of all this evidence of cardboard’s supportive relationship with capitalism, and in spite of the assurances that figures writers like Ley and Bettendorf offered above, cardboard has now become an emblem of things-gone-wrong, economically and otherwise. With a single shot of a greasy, cheese-congealed pizza box, a movie can establish that a character is subsisting in domestic disarray. On the evening news and crime dramas, at least since the early 1990s, we frequently see images of cardboard homes erected on curbs by the homeless—people who cannot not afford the items shipped in the very containers that Alan Greenspan took as an indicator of economic plenty.

Already in the late 19th century, “cardboard” had become a synonym for “flimsy.” The Oxford English Dictionary notes a crucial usage in 1893, in which an English author discussed the European heritage of certain cultures in India. As part of his historical investigation, he summarizes the growth and collapse of Alexander the Great’s empire in Asia: when the empire had reached the point of maximum expansion, with insufficient military power to back it up, Alexander’s “cardboard empire of the East fell to pieces.”(4) It appears that cardboard—the material that some would credit as the basis of capitalism’s imperial expansion and which some would claim as the one thing that separated civilized man from “coolie” colonial others—is the material that best captures empire’s lack of substance.

What else could Goff make of cardboard, then, but a Lincoln Continental Mark V—the gas-guzzling behemoth of 1979 that was sign of the American car industry’s empire, its hubris and failure. Consider the narrative arc suggested by the following, highly selective chronology of the Continental:

1964: A reporter from Time Magazine writes about accompanying Lyndon Johnson on one of his famous 90-mile-an-hour joyrides across his Texas ranch in a Lincoln Continental. (5)

1965: Joe Namath, who is scooped up by the Jets as a first-round draft pick, stipulates that his contract include a Lincoln Continental.

1972: President Nixon acquires an armor-plated Lincoln Continental that is tricked out with a 460 cubic inch, 214 horsepower V-8 engine, a fourteen unit “aerospace type control panel,” explosion and fire-resistant foam bladder fuel tanks of the type used in airplanes and race cars, and miniature spotlights to illuminate the president’s fender flags at night. Experts estimate it cost about half a million dollars. (6)

1976: CBS cancels the primetime detective series entitled Cannon, in which the namesake character—a gluttonous private dick played by William Conrad—drives a Lincoln Continental Mark IV.

1979: As a response to oil shortages of previous years, Lincoln tries to improve mileage by shrinking the chassis size of the Continental Mark series. The Lincoln Continental Mark V (last made in 1979) would be the last model to be bigger than the previous one.

1986: The Beastie Boys drop a tune entitled The New Style, a hip hop anthem to Jersey taste that nestles Lincoln’s signature car in a now familiar nexus of New Jersey cheesiness: “I chill at White Castle cause it’s the best / But I’m fly at Fatburger when I’m out west / Went to the prom in my fly blue rental / Got six girlies in my Lincoln Continental.”

1994: Vince Vega, an aging assassin (played similarly post-prime John Travolta) inadvertently shoots a young colleague in his Lincoln Continental, splattering his brains all over the back seat.

This story of the Continental Mark series (like the story of the American Dream) begins with freedom and success, only to slouch into over-indulgence and lapse into paranoid over-defensiveness. It enters middle age, reevaluates previous goals. It degrades into the haze of nostalgia, becomes the butt of bitter humor. And so it is that, from presidents to pimps, a Lincoln from the seventies is today understood to be the car of ill-gotten wealth and/or doomed aspirations.

But it would be a mistake to suggest that Goff’s car is merely an indictment of consumer culture. Her personal investment in, and affection, for her hometown of Detroit makes such a reductive story impossible. And indeed, her car is full of anomalies and idiosyncrasies. Her car is not so much the simulacrum of a commodity, but rather an intimate reimagining. As one person making a single car, Goff has been both designer and laborer. While she might have escaped the alienation of assembly line work through which cars and cardboard are typically produced, she has developed an extraordinarily intense relationship to her material and the object she made of it. Her massive hulk of a car consists of obsessive, meticulous gestures made in love and admiration, as well as boredom and frustration. With her repetitive cutting, piecing, and gluing, Goff might seek the more surprising stories can a material like cardboard can provide.

I imagine that the artist might have wavered between fondness and fatigue when looking at cardboard’s warm, bland color. She may have come to despise the matte surface (so un-carlike) that makes paint lie on cardboard in uneven streaks. At moments she may have been inconvenienced by the planar tilt and tumble through with which a sheet of cardboard takes its time falling to the floor. And what of cardboard’s straw-like aroma, its tiny fibers that spray into the air when ripped, its edges that, when fine, can cut the hands, or, when rough, abrade them?